Tuscany

Toscana produces just under 3 million hl/79 million gal of wine a year. The Tuscan countryside is famously undulating. A full 68 per cent of the region is officially classified as hilly (a mere 8 per cent of the land is flat) and hillside vineyards, at altitudes of between 150 and 500 m (500–1,600 ft) supply the vast majority of the better-quality wines. The sangiovese vine, the backbone of the region's production, seems to require the concentration of sunlight that slopes can provide to ripen well in these latitudes, as well as the less fertile soils on the hills. Growers also value the significant temperature variability between day and night as an important factor in developing its aromatic qualities.

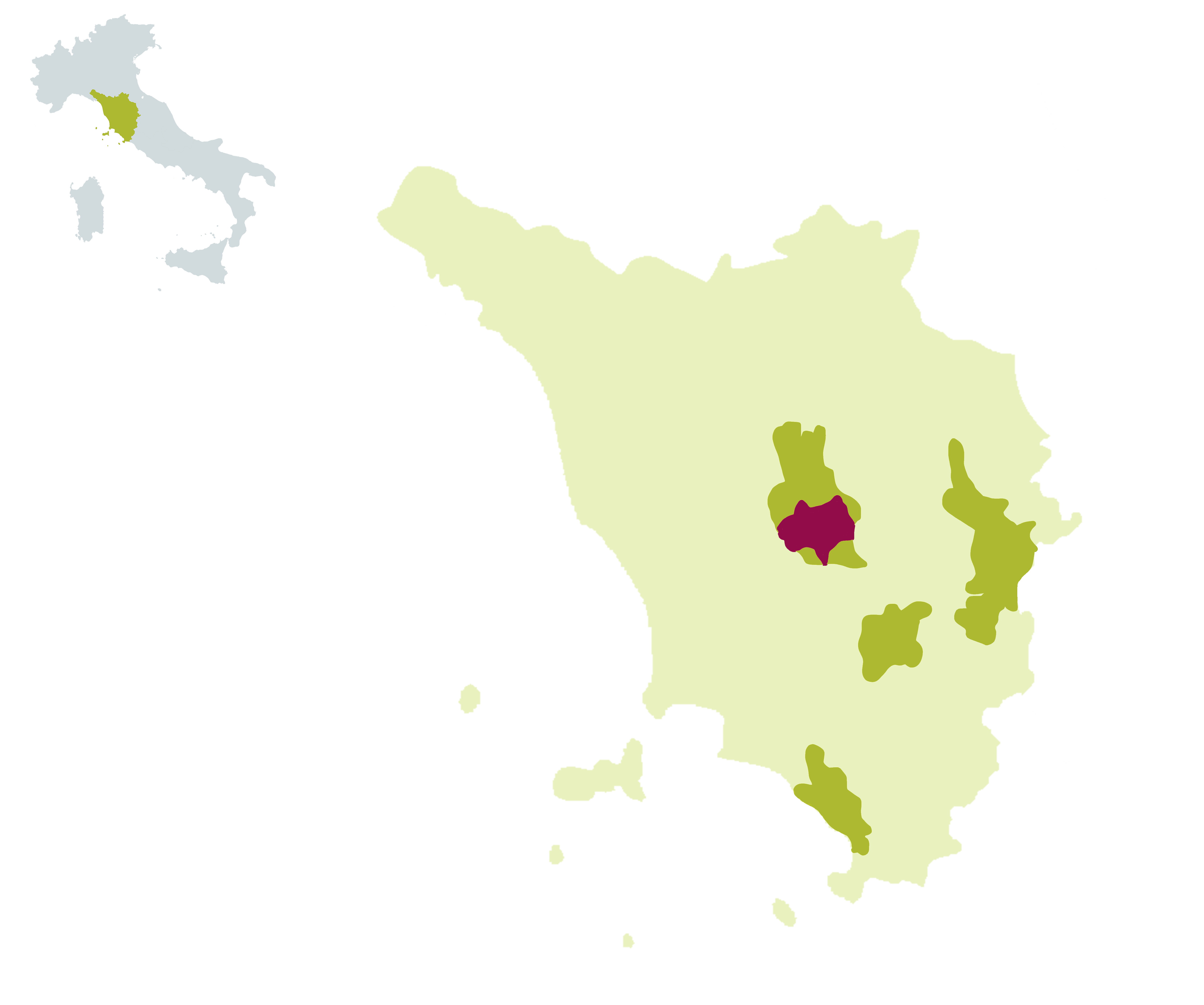

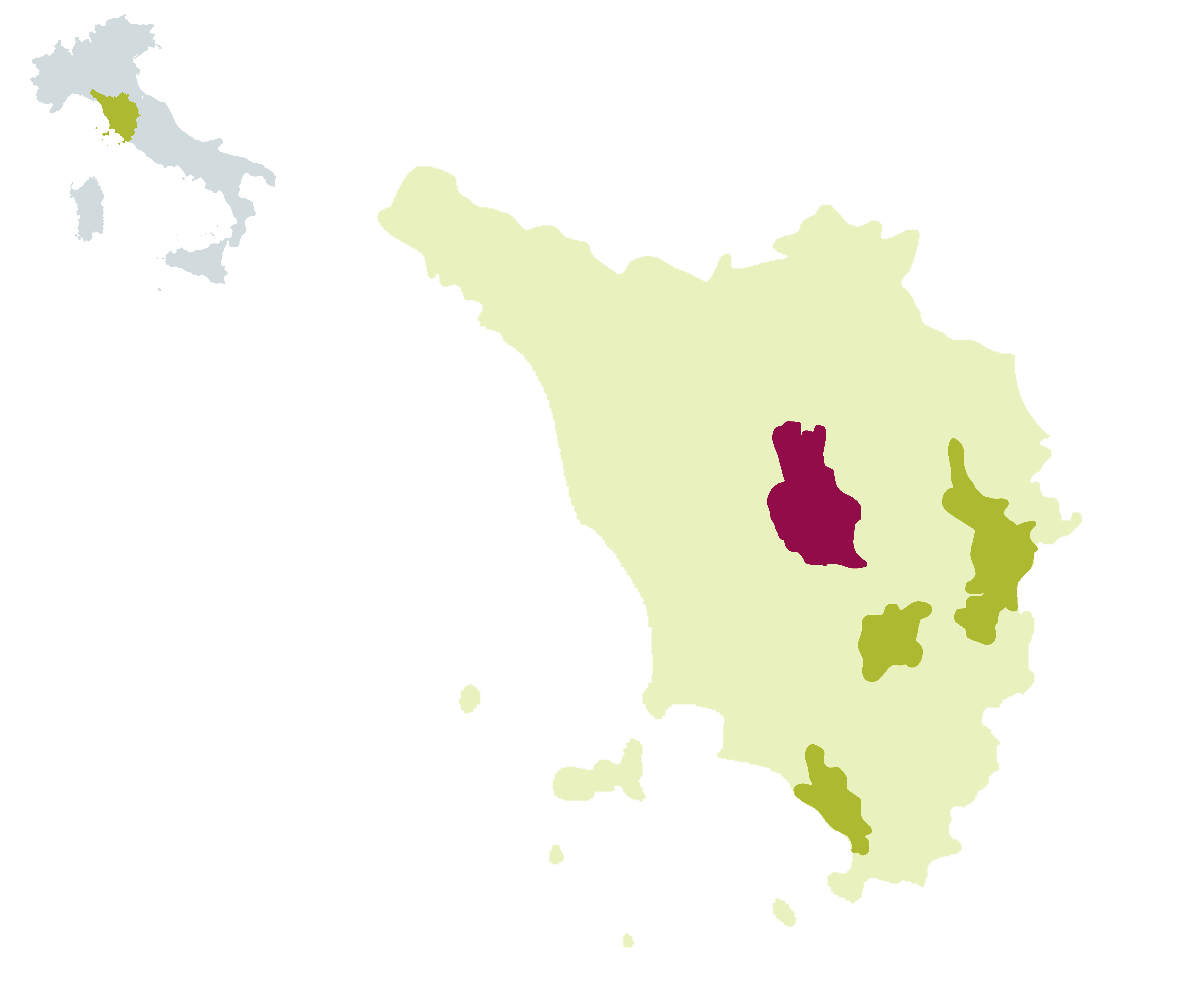

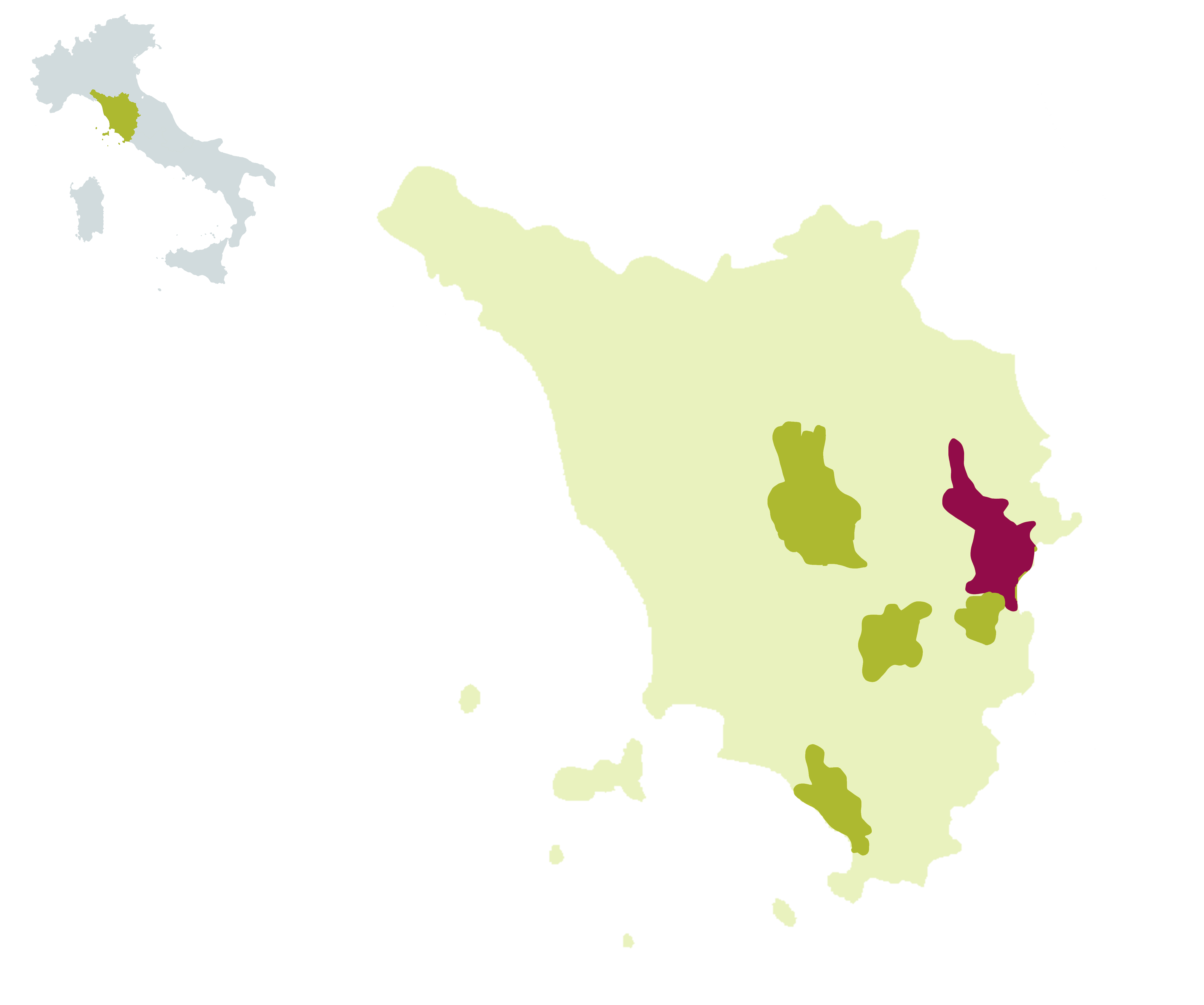

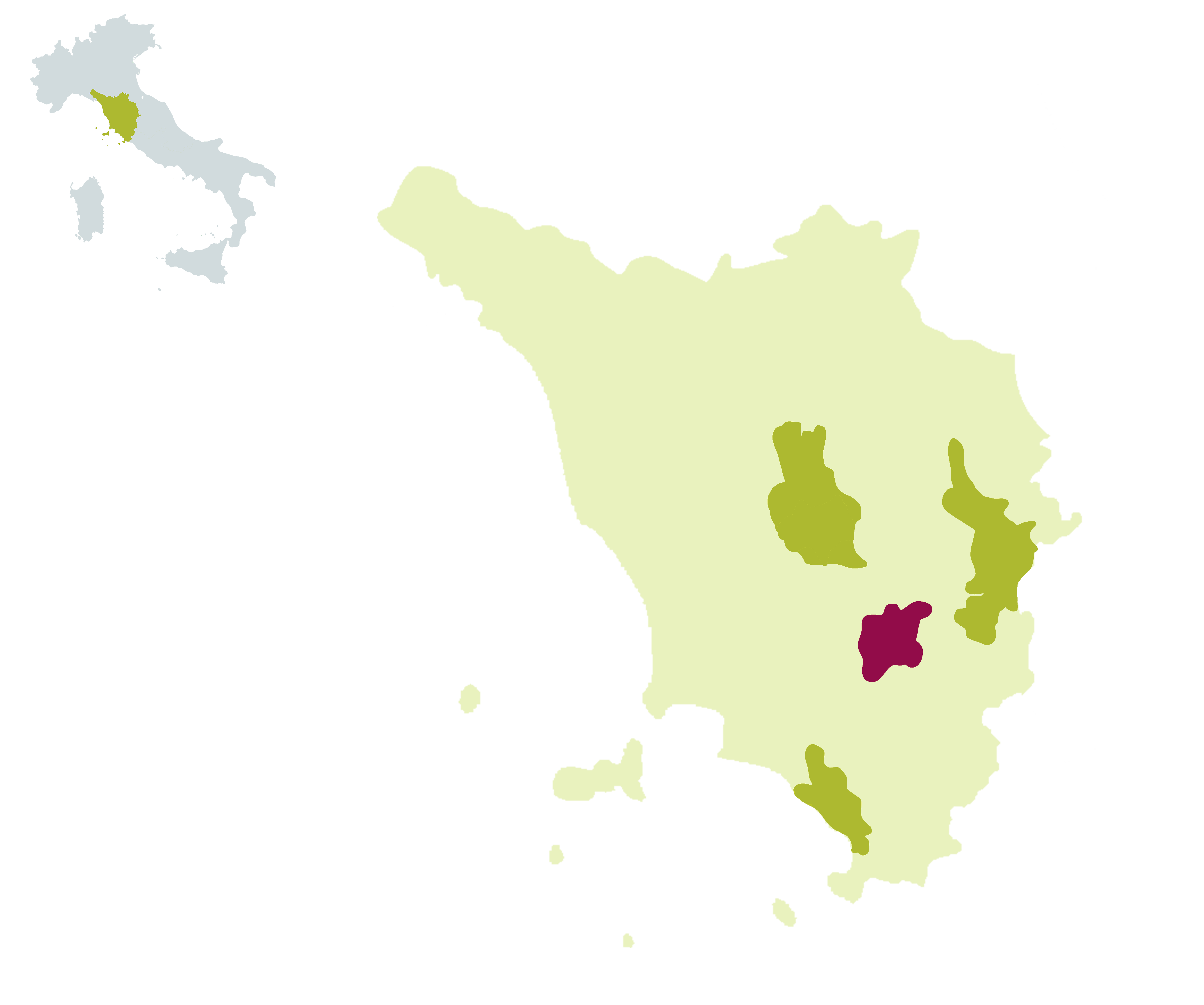

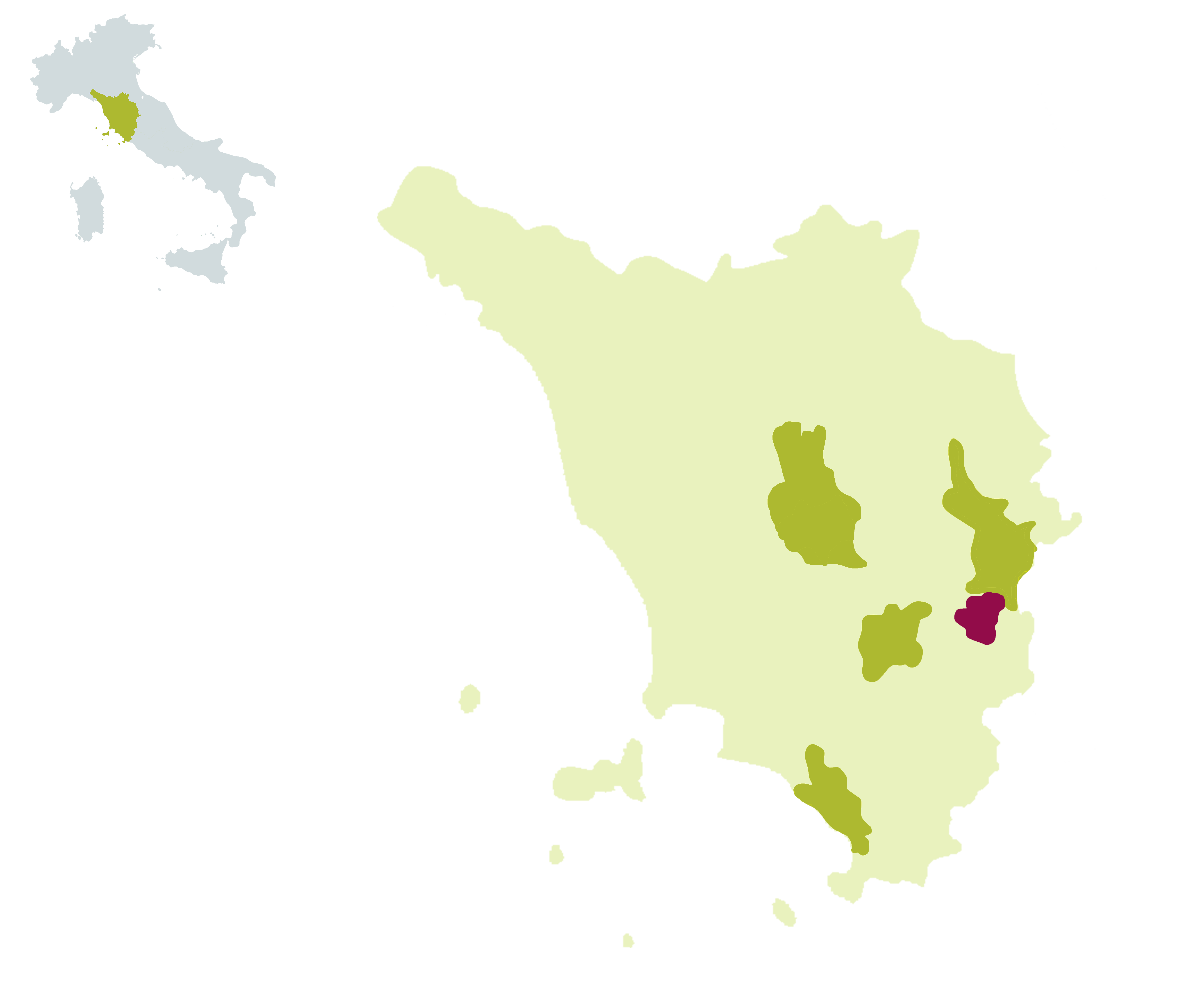

Sangiovese has been, until recently, virtually synonymous with fine wine in Toscana and, although the variety is widely planted throughout central Italy, the Tuscan climate (harsh in winter) and the calcium-rich marls in the best zones have thus far given incomparable results for this variety. From Carmignano, Rufina, and the hills around Vinci in the north through the chianti classico area to the zones of vino nobile di montepulciano and brunello di montalcino, Sangiovese is the recurring theme in Tuscan wine although it has traditionally been blended with such other varieties as Canaiolo, Malvasia, and, in the 20thcentury, Trebbiano. Since the 1980s, however, attempts have been made to make great wines from Sangiovese alone. The pursuit of quality that began in earnest in the late 1970s in Chianti Classico and Montepulciano focused on Sangiovese, but producers soon discovered that the wave of enthusiasm that followed the introduction of the DOC laws in the late 1960s had resulted in large plantings of unsuitable clones on poor rootstocks in many unsuitable sites. The past 25 years has seen a series of small steps to redress this situation, and many new vineyards now have far superior clones of Sangiovese, and are producing infinitely better wines as a result.

Tuscan viticulture was dominated historically by large estates owned by wealthy local families, the majority of them of noble origin, and tilled by a workforce of sharecroppers. The demise of this system in the 1950s and 1960s led to a hiatus in investment or even ordinary maintenance, deterioration of the vineyards and cellars, plummeting quality, and eventual sales of the properties to new owners with the requisite capital and energy to carry on the viticultural traditions of the past. Tuscan ownership of Tuscan viticulture is now part of history, but the new wave of vintners from Milan, Rome, and Genoa—joined in the 1980s by a sizeable contingent of foreigners—has shown both a commendable commitment to quality and an equally commendable openness to new and more cosmopolitan ideas. See also antinori, frescobaldi, and ricasoli, local noble families with considerable wine interests.

White Wines

Trebbiano has been for white wine what Sangiovese has been for red wine, the basis of the regional production, and more than a dozen Trebbiano-based doc wines currently exist in Toscana. The grape has been cultivated principally for its high productivity and its acid-conserving qualities in hot areas, plus its resistance to frost in cool, damp areas, but the wines have little character and have gradually gone out of fashion in the market place; they seem destined to be used exclusively for vin santo. Scattered patches of vermentino exist along the Tuscan coast up to the border with Liguria, but the variety has yet to establish a clear identification with Toscana as a region. Interest in white wines was strong in the 1980s, however, and pioneering producers in Chianti experimented with white international varieties—principally chardonnay and sauvignon—in higher vineyards where Sangiovese ripens poorly. Results have been mixed thus far, with only a handful of Chardonnays of note.

Supertuscans

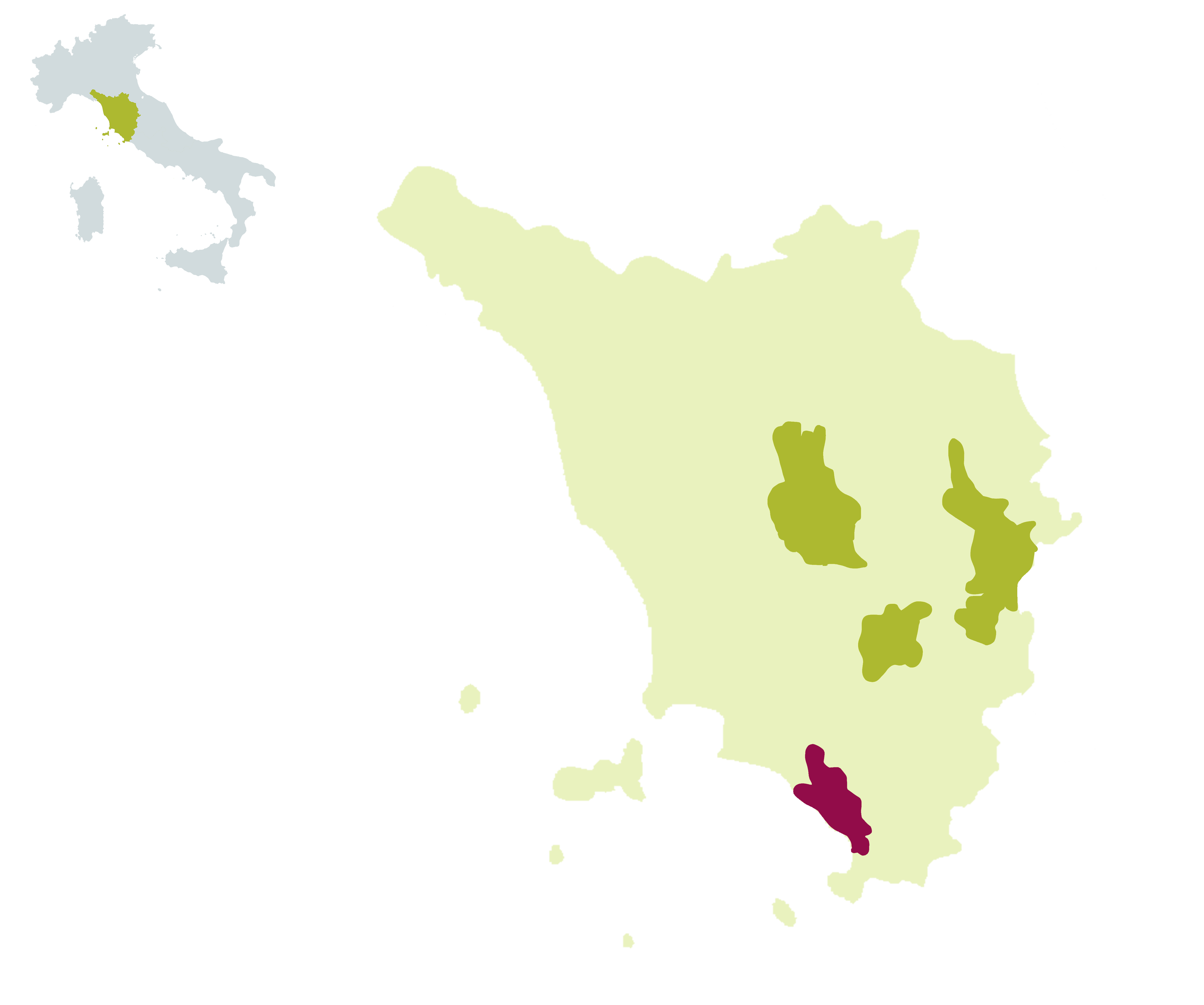

Far less marginal are the new breed of Tuscan red wines, the so-called Supertuscans, often made with the assistance of Frenchvine varieties and in an international style. Their development dates from the late 1960s and early 1970s, first as experiments or even for mere divertissement, but the startling results obtained in such all-cabernet wines as Sassicaia and such Sangiovese/Cabernet blends as Tignanello from antinori have established these products as a fundamental category in the overall Tuscan picture. Few estates in Chianti have not joined in the scramble to produce a wine of this prestigious type, and small barrel maturation, now extended to Sangiovese, has yielded a new style of Tuscan wine greatly appreciated by consumers who once disdained Chianti. merlot is increasingly planted as an alternative to Cabernet, with impressive results, and in the 1990s significant amounts of syrah vines began to bear fruit, with uneven results.

Chianti still towers over these new wines, none the less. With over 900,000 hl/23.7 million gal produced in an abundant year, it is Italy's largest single group of DOCGs (although it should be remembered that Chianti's name has been extended to subzones near Florence, Pisa, Pistoia, Arezzo, and Siena which have nothing to do with the historic zone of Chianti Classico between Florence and Siena).

References:

, Vino Italiano: The Regional Wines of Italy (New York, 2002).

, From Brunello to Zibibbo: The Wines of Southern Italy (London, 2001).